Follow the case for voting reform in these concise pages

The Dangers of Gerrymandering

There is another structural defect of First-past-the-post as used for UK Parliamentary elections and that is the requirement that communities be chopped up into artificial single member constituencies with, as far as possible, an equal number of voters in each. This is a futile exercise which requires regular reworks to accommodate constant movement of population. A House of Commons Library report of October 2019 states that: “On average, there were 70,858 people registered to vote in parliamentary elections in constituencies in England and Wales in 2018. However, this figure hides big differences between constituencies. The smallest constituency, Arfon, had 38,864 voters, while the biggest, Isle of Wight, had 108,125.” Clearly, it is unfair and undemocratic that Arfon votes are nearly three times more powerful than those cast on the Isle of Wight.

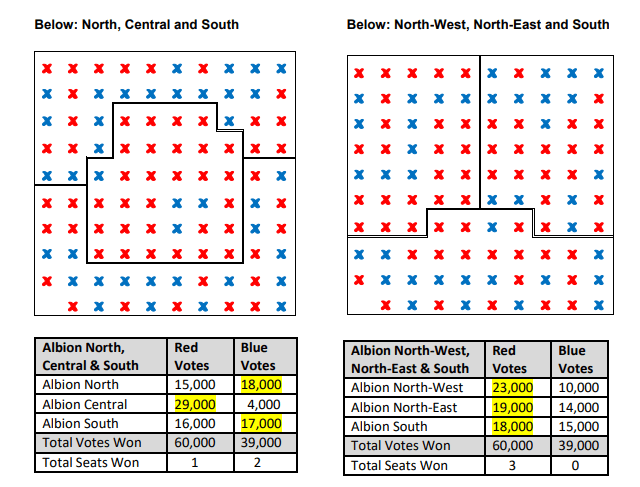

Moreover, where these boundaries are drawn can make a difference to an election result. To return to the Albion model we used earlier, the two boxes of Xs below represent 2 different configurations of the City of Albion, with each X representing one thousand voters, coloured according to support for the two Red and Blue parties. The location of the voters and the way they vote is exactly the same in both models. The City is big enough to warrant 3 MPs so it has to be divided into 3 constituencies, each returning one MP, and the two diagrams and tables below represent two different sets of proposals and their consequences:

As can be seen, it is possible to draw the Albion City boundaries in different ways so as to allow for exactly the same number of voters in each of the three constituencies. The problem is, the election results in the two configurations above are completely different; in the first option, the Blues take the most seats with fewer votes than the Reds, while in the second option, they win no seats at all.

The potential for mischief is obvious and, while independent boundary commissions will use best endeavours to keep the redrawing of boundaries free from what is known as gerrymandering – manipulating boundaries for political gain – controversy is never very far away.

The Boundary Commission for Northern Ireland, for example, got themselves into a spot of bother a few years ago while trying to redraw the province’s parliamentary boundaries as part of a review; when the Commission’s “Secondary Proposals” were published in 2017, the data from that year’s general election results was extrapolated using the projected new boundaries in order to establish what the June 2017 result would have been with the new boundaries in place. The Democratic Unionists, having polled 36% of the vote, would have taken 41% of the seats under the Commission’s proposals, while Sinn Fein with 29% of the vote would have taken 53% of the seats. Understandably, the Unionists were not happy, so the Commission had another go and published some “Revised Proposals” which were then subject to the same “what if?“ exercise. This revealed that, under the revised scheme, the Democratic Unionists would have won 59% of the seats in 2017 while Sinn Fein would have taken 41% of the seats. It seems that everybody could vote exactly the same in exactly the same locations and yet there would be a completely different result, simply by re-drawing the single member constituency boundaries. Needless to say, the Nationalists accused the Commission of gerrymandering and of caving in to Unionist pressure.

There is a device known as “the Gerrymander Wheel” which demonstrates how altering single-member constituency boundaries can affect election results in a three-party situation. This is available to view at https://stvact.files.wordpress.com/2013/08/gerrymander_wheel.pdf

We need to be rid of single member constituencies.